Kumaravadivelu argued that a post method pedagogy must (a) facilitate

the advancement of a context-sensitive language education based on a true

understanding of local linguistic, socio-cultural, and political

particularities; (b) rupture the reified role relationship between theorists

and practitioners by enabling teachers to construct their own theory of

practice; and (c) tap the sociopolitical consciousness that participants bring

with them in order to aid their quest for identity formation and social transformation.

Treating

learners, teachers, and teacher educators as coexplorers, Kumaravadivelu

discusses their roles and functions in a post-method pedagogy. He concludes by

raising the prospect of replacing the limited concept of method with the three pedagogic

parameters of particularity, practicality, and possibility as organizing

principles for L 2 teaching and teacher education.

In this very

assignment, I am going to highlight post-method condition, post-method

pedagogy, pedagogic parameters, pedagogic frameworks, advantages and

disadvantages of post-method pedagogy, negative and positive criticisms on

post-method pedagogy and conclusion.

Post-method

Condition

The post-method

condition signifies three interrelated attributes. First and foremost, it

signifies a search for an alternative to method rather than an alternative

method. While alternative methods are primarily products of top-down processes,

alternatives to method are mainly products of bottom-up processes. In practical

terms, this means that we need to refigure the relationship between the

theorizer and the practitioner of language teaching. If the conventional

concept of method entitles theorizers to construct professional theories of

pedagogy, the post-method condition empowers practitioners to construct

personal theories of practice. If the concept of method authorizes theorizers

to centralize pedagogic decision-making, the post-method condition enables

practitioners to generate location-specific, classroom-oriented innovative strategies.

Secondly, the

post-method condition signifies teacher autonomy. The conventional concept of

method “overlooks the fund of experience and tacit knowledge about teaching

which the teachers already have by virtue of their lives as students” (Freeman,

1991, p. 35). The post-method condition, however, recognizes the teachers’

potential to know not only how to teach but also how to act autonomously within

the academic and administrative constraints imposed by institutions, curricula,

and textbooks. It also promotes the ability of teachers to know how to develop

a critical approach in order to self-observe, self-analyze, and self-evaluate

their own teaching practice with a view to effecting desired changes.

The third

attribute of the post-method condition is principled pragmatism. Unlike

eclecticism which is constrained by the conventional concept of method, in the

sense that one is supposed to put together practices from different established

methods, principled pragmatism is based on the pragmatics of pedagogy where “the

relationship between theory and practice, ideas and their actualization, can

only be realized within the domain of application, that is, through the

immediate activity of teaching” (Widdowson, 1990, p. 30). Principled pragmatism

thus focuses on how classroom learning can be shaped and reshaped by teachers

as a result of self-observation, self-analysis, and self-evaluation.

One way in which

teachers can follow principled pragmatism is by developing what Prabhu (1990)

calls “a sense of plausibility.” Teachers’ sense of plausibility is their

“subjective understanding of the teaching they do” (Prabhu, 1990, p. 172). This

subjective understanding may arise from their own experience as learners and

teachers, and through professional education and peer consultation. Since

teachers’ sense of plausibility is not linked to the concept of method, an

important concern is “not whether it implies a good or bad method, but more

basically, whether it is active, alive, or operational enough to create a sense

of involvement for both the teacher and the student” (Ibid., p. 173).

The three major

attributes of the post-method condition outlined above provide a solid

foundation on which the fundamental parameters of a post-method pedagogy can be

conceived and constructed.

Post-method

Pedagogy

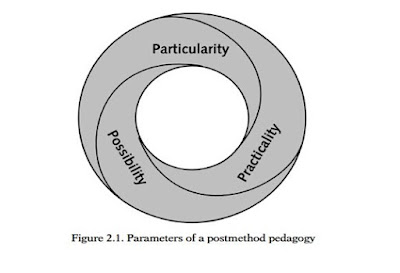

Post-method pedagogy

allows us to go beyond, and overcome the limitations of method-based pedagogy.

Incidentally, the term pedagogy in a broad sense,

to include not only issues pertaining to classroom strategies, instructional

materials, curricular objectives, and evaluation measures but also a wide range

of historio-political and socio-cultural experiences that directly or indirectly

influence L2 education. Within such a broad-based definition, post-method

pedagogy can be visualized as a three-dimensional system consisting of

pedagogic parameters of particularity, practicality, and possibility. I briefly

outline below the salient features of each of these parameters indicating how

they interweave and interact with each other.

The Parameter of Particularity

The parameter of

particularity requires that any language pedagogy, to be relevant, must be sensitive

to a particular group of teachers teaching a particular group of learners

pursuing a particular set of goals within a particular institutional context

embedded in a particular socio-cultural milieu. The parameter of particularity

then is opposed to the notion that there can be an established method with a

generic set of theoretical principles and a generic set of classroom practices.

From a pedagogic point of view, then, particularity is at once a goal and a

process. That is to say, one works for

and through particularity

at the same time. It is a progressive advancement of means and ends. It is the

ability to be sensitive to the local educational, institutional and social

contexts in which L2 learning and teaching take place. It starts with

practicing teachers, either individually or collectively, observing their

teaching acts, evaluating their outcomes, identifying problems, finding

solutions, and trying them out to see once again what works and what doesn’t.

Such a continual cycle of observation, reflection, and action is a prerequisite

for the development of context-sensitive pedagogic theory and practice. Since

the particular is so deeply embedded in the practical, and cannot be achieved

or understood without it, the parameter of particularity is intertwined with

the parameter of practicality as well.

The Parameter of Practicality

The parameter of

practicality relates to a much larger issue that directly impacts on the

practice of classroom teaching, namely, the relationship between theory and

practice. The parameter of practicality entails a teacher-generated theory of

practice. It recognizes that no theory of practice can be fully useful and

usable unless it is generated through practice. A logical corollary is that it

is the practicing teacher who, given adequate tools for exploration, is best

suited to produce such a practical theory. The intellectual exercise of

attempting to derive a theory of practice enables teachers to understand and

identify problems, analyze and assess information, consider and evaluate

alternatives, and then choose the best available alternative that is then

subjected to further critical appraisal. In this sense, a theory of practice

involves continual reflection and action. If teachers’ reflection and action

are seen as constituting one side of the practicality coin, their insights and

intuition can be seen as constituting the other. Sedimented and solidified

through prior and ongoing encounters with learning and teaching is the

teacher’s unexplained and sometimes unexplainable awareness of what constitutes

good teaching. Teachers’ sense-making (van Manen, 1977) of good teaching

matures over time as they learn to cope with competing pulls and pressures

representing the content and character of professional preparation, personal

beliefs, institutional constraints, learner expectations, assessment

instruments, and other factors. The seemingly instinctive and idiosyncratic

nature of the teacher’s sense-making disguises the fact that it is formed and

reformed by the pedagogic factors governing the microcosm of the classroom as

well as by the sociopolitical forces emanating from outside. Consequently,

sense-making requires that teachers view pedagogy not merely as a mechanism for

maximizing learning opportunities in the classroom but also as a means for

understanding and transforming possibilities in and outside the classroom. In

this sense, the parameter of practicality metamorphoses into the parameter of

possibility.

The parameter of

possibility is derived mainly from the works of critical pedagogists of

Freirean persuasion. Critical pedagogists take the position that any pedagogy

is implicated in relations of power and dominance, and is implemented to create

and sustain social inequalities. They call for recognition of learners’ and

teachers’ subject-positions, that is, their class, race, gender, and ethnicity,

and for sensitivity toward their impact on education. In the process of

sensitizing itself to the prevailing sociopolitical reality, the parameter of

possibility is also concerned with individual identity. More than any other

educational enterprise, language education provides its participants with

challenges and opportunities for a continual quest for subjectivity and self-identity

for, as Weeden (1987, p. 21) points out, “Language is the place where actual

and possible forms of social organization and their likely social and political

consequences are defined and contested. Yet it is also the place where our

sense of ourselves, our subjectivity, is constructed.” This is even more

applicable to L2 education, which brings languages and cultures in contact. To

sum up this section, I have suggested that one way of conceptualizing a post-method

pedagogy is to look at it three-dimensionally as a pedagogy of particularity,

practicality, and possibility. The parameter of particularity seeks to

facilitate the advancement of a context-sensitive, location-specific pedagogy

that is based on a true understanding of local linguistic, socio-cultural, and

political particularities. The parameter of practicality seeks to rupture the

reified role relationship by enabling and encouraging teachers to theorize from

their practice and to practice what they theorize. The parameter of possibility

seeks to tap the sociopolitical consciousness that participants bring with them

to the classroom so that it can also function as a catalyst for a continual

quest for identity formation and social transformation. Inevitably, the

boundaries of the particular, the practical, and the possible are blurred.

As Figure 2.1

shows, the characteristics of these parameters overlap. Each one shapes and is

shaped by the other. They interweave and interact with each other in a synergic

relationship where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. The result

of such a relationship will vary from context to context depending on what the

participants bring to bear on it.

If we assume

that the three pedagogic parameters of particularity, practicality, and

possibility have the potential to form the foundation for a post-method

pedagogy, and propel the language teaching profession beyond the limited and

limiting concept of method, then we need a coherent framework that can guide us

to carry out the salient features of the pedagogy in a classroom context. I

present below one such framework—a macrostrategic framework (Kumaravadivelu,

1994a).

Macrostrategic

Framework

The

macrostrategic framework for language teaching consists of macrostrategies and

microstrategies. Macrostrategies are defined as guiding principles derived from

historical, theoretical, empirical, and experiential insights related to L2

learning and teaching. A macrostrategy is thus a general plan, a broad

guideline based on which teachers will be able to generate their own

situation-specific, need-based microstrategies or classroom techniques. In

other words, macrostrategies are made operational in the classroom through microstrategies.

The suggested macrostrategies and the situated microstrategies can assist L2

teachers as they begin to construct their own theory of practice.

Macrostrategies

may be considered theory-neutral as well as method-neutral. Theory-neutral does

not mean atheoretical; rather it means that the framework is not constrained by

the underlying assumptions of any one particular professional theory of

language, language learning, or language teaching. Likewise, method-neutral does

not mean methodless; rather it means that the framework is not conditioned by

any of the particular set of theoretical principles or classroom procedures

normally associated with any of the particular language teaching methods

discussed in the early part of this chapter.

Ten

Macrostrategies as suggested by Kumaravadivelu are as follows-

1. Maximize

learning opportunities: This macrostrategy envisages teaching as a

process of creating and utilizing learning opportunities, a process in which

teachers strike a balance between their role as managers of teaching acts and

their role as mediators of learning acts.

2. Facilitate

negotiated interaction: This macrostrategy refers to meaningful

learner-learner, learner-teacher classroom interaction in which learners are

entitled and encouraged to initiate topic and talk, not just react and respond.

3. Minimize

perceptual mismatches: This macrostrategy emphasizes the recognition

of potential perceptual mismatches between intentions and interpretations of

the learner, the teacher, and the teacher educator.

There are ten

sources of perpetual mismatches-

A) Cognitive B)

Pedagogy C) Evaluate D) Communicative E) Strategic F) Procedural G) Linguistic

H) Cultural I) Instructional J) Attitudinal

4. Activate

intuitive heuristics: This macrostrategy highlights the importance

of providing rich textual data so that learners can infer and internalize

underlying rules governing grammatical usage and communicative use. It also

encourages self-discovery and self-learning.

5. Foster

language awareness: This macrostrategy refers to any attempt to draw

learners’ attention to the formal and functional properties of their L2 in

order to increase the degree of explicitness required to promote L2 learning.

6. Contextualize

linguistic input: This macrostrategy highlights how language

usage and use are shaped by linguistic, extralinguistic, situational, and

extrasituational contexts.

7. Integrate

language skills: This macrostrategy refers to the need to

holistically integrate language skills traditionally separated and sequenced as

listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

8. Promote learner autonomy: This

macrostrategy involves helping learners learn how to learn, equipping them with

the means necessary to self-direct and self-monitor their own learning.

9. Raise

cultural consciousness: This macrostrategy emphasizes the need to

treat learners as cultural informants so that they are encouraged to engage in

a process of classroom participation that puts a premium on their

power/knowledge.

10. Ensure

social relevance: This macrostrategy refers to the need for teachers

to be sensitive to the societal, political, economic, and educational

environment in which L2 learning and teaching take place.

From the wheel,

we can agree that the ten macrostrategies are typically in a systemic relationship,

supporting one another. That is to say, a particular macrostrategy is connected

with and is related to a cluster of other macrostrategies. Clustering of

macrostrategies may be useful depending on specific teaching objectives for a

given day of instruction. When teachers have an opportunity to process and

practice their teaching through a variety of macrostrategies, they will

discover how they all hang together.

Advantages

·

The Post-method era lets us learn and understand different

methods and approaches and also takes from them different elements to build up

our own.

·

As

a teacher, we have to make our selection and analyses taking into account the

needs and interests of the student.

Disadvantages

·

As methods are prescribed, teachers sometimes cannot work

freely.

·

Methods

and approaches are not culturally universal so they cannot be applied in any

culture. If we want to apply them, we have to take into account the social,

cultural, political context.

Criticisms on Post-method

Pedagogy

Positive Criticisms:

1.

Post-method pedagogy is “a compelling idea that emphasizes greater judgment

from teachers in each context and a better match between the means and the

ends” (Crabbe, 2003: 16)

2.

It encourages the teacher “to engage in a carefully crafted process of

diagnosis, treatment, and assessment” (Brown, 2002: 13).

3.

“It also provides one possible way to be responsive to be lived experiences of

learners and teachers, and to the local exigencies of learning and teaching”

(Kumaravadivelu, 2006a: 73).

Negative

Criticisms:

1.

Post-method is not an alternative to method but only an addition to method

(Liu, 1995).

2.

Questioning the very concept of post-method pedagogy: “Kumaravadivelu’s

macrostrategies constitute a method” (Larsen-Freeman, 2005: 24).

3.

Bell (2003) laments that “by deconstructing methods, post-method pedagogy has

tended to cut teachers off from their sense of plausibility, their passion and

involvement”.

Requirements

for implementation of post-method pedagogy

·

Teachers

construct self-reflections

·

Teachers’

centrality in developing ELT.

·

Teacher

education and development programs.

Conclusion

There are at

least three broad, overlapping strands of thought that emerge from what we have

discussed so far. First, the traditional concept of method with its generic set

of theoretical principles and classroom techniques offers only a limited and

limiting perspective on language learning and teaching. Second, learning and

teaching needs, wants, and situations are unpredictably numerous. Therefore,

current models of teacher education programs can hardly prepare teachers to

tackle all these unpredictable needs, wants, and situations. Third, the primary

task of in-service and pre-service teacher education programs is to create

conditions for present and prospective teachers to acquire the necessary

knowledge, skill, authority, and autonomy to construct their own personal pedagogic

knowledge. Thus, there is an imperative need to move away from a method-based

pedagogy to a post-method pedagogy.

One possible way

of conceptualizing and constructing a post-method pedagogy is to be sensitive

to the parameters of particularity, practicality, and possibility, which can be

incorporated in the macrostrategic framework. The framework, then, seeks to

transform classroom practitioners into strategic thinkers, strategic teachers,

and strategic explorers who channel their time and effort in order to-

·

reflect

on the specific needs, wants, situations, and processes of learning and

teaching

·

stretch

their knowledge, skill, and attitude to stay informed and involved

·

design

and use appropriate microstrategies to maximize learning potential in the

classroom

·

monitor

and evaluate their ability to react to myriad situations in meaningful ways.

In short, the

framework seeks to provide a possible mechanism for classroom teachers to begin

to theorize from their practice and practice what they theorize.

Good summary of Post Method Era.

উত্তরমুছুন